More Than Money: Correlation Among Worker Demographics, Motivations, and Participation in Online Labor Market

—Wei-Chu Chen, Siddharth Suri, and Mary L. Gray in The 13th International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM), Munich, Germany, May 2019

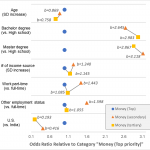

Most prior research about online labor markets examines the dynamics of a single work platform and either worker demographics or motivations associated with that site. How demographics and motives correlate with each other, and with engagement across multiple platforms, remains under-studied. To bridge this gap, we analyze survey responses from 1700 people working across four different online labor platforms to understand: What motivates people to participate in online labor markets and how do individual motives correspond to larger demographic patterns and structural dynamics that more broadly shape traditional employment opportunities? Our results show that age, gender, education, and number of income sources help explain who does on-demand work, when they do it, and why. Even more striking, these broader social dimensions of work correlate with when and why individuals work across multiple on-demand platform companies. Together, these factors structure on-demand labor markets more than individual choice or the presumed “flexibility” of on-demand work alone.

The Humans Working Behind the AI Curtain

—Mary L. Gray, Siddharth Suri in The Harvard Business Review

Whether it is Facebook’s trending topics; Amazon’s delivery of Prime orders via Alexa; or the many instant responses of bots we now receive in response to consumer activity or complaint, tasks advertised as AI-driven involve humans, working at computer screens, paid to respond to queries and requests sent to them through application programming interfaces (APIs) of crowdwork systems. The truth is, AI is as “fully-automated” as the Great and Powerful Oz was in that famous scene from the classic film, where Dorothy and friends realize that the great wizard is simply a man manically pulling levers from behind a curtain.

Running Out of Time: The Impact and Value of Flexibility in On-Demand Crowdwork

—Ming Yin, Siddharth Suri, and Mary L. Gray in The 36th ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI), Montreal, Canada, April 2018

—Ming Yin, Siddharth Suri, and Mary L. Gray in The 36th ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI), Montreal, Canada, April 2018

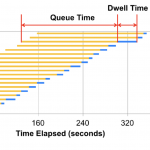

With a seemingly endless stream of tasks, on-demand labor markets appear to offer workers flexibility in when and how much they work. This research argues that platforms afford workers far less flexibility than widely believed. A large part of the “inflexibility” comes from tight deadlines imposed on tasks, leaving workers little control over their work schedules. We experimentally examined the impact of offering workers control of their time in on-demand crowdwork. We found that granting higher “in-task flexibility” dramatically affected the temporal dynamics of worker behavior and produced a larger amount of work with similar quality. In a second experiment, we measured the compensating differential and found that workers would give up significant compensation to control their time, indicating workers attach substantial value to in-task flexibility. Our results suggest that designing tasks which give workers direct control of their time within tasks benefits both buyers and sellers of on-demand crowdwork.

The Communication Network Within the Crowd

—Ming Yin, Mary L. Gray, Siddharth Suri, Jennifer Wortman Vaughan in The 25th International World Wide Web Conference (WWW), Montreal, Canada, April 2016

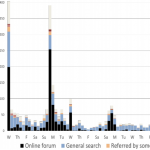

Since its inception, crowdsourcing has been considered a black-box approach to solicit labor from a crowd of workers. Prior work has shown the existence of edges between workers. We build on and extend this discovery by mapping the entire communication network of workers on Amazon Mechanical Turk, a leading crowdsourcing platform. We execute a task in which over 10,000 workers from across the globe self-report their communication links to other workers, thereby mapping the communication network among workers. Our results suggest that while a large percentage of workers indeed appear to be independent, there is a rich network topology over the rest of the population. That is, there is a substantial communication network within the crowd. We further examine how online forum usage relates to network topology, how workers communicate with each other via this network, how workers’ experience levels relate to their network positions, and how U.S. workers difer from international workers in their network characteristics. We conclude by discussing the implications of our findings for requesters, workers, and platform providers like Amazon.

The Crowd is a Collaborative Network

—Mary L. Gray, Siddharth Suri, Syed Shoaib Ali, and Deepti Kulkarni in Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, CSCW 2016, pages 134–147

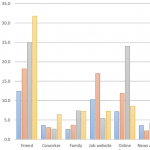

The main goal of this paper is to show that crowdworkers collaborate to fulfill technical and social needs left by the platform they work on. That is, crowdworkers are not the independent, autonomous workers they are often assumed to be, but instead work within a social network of other crowdworkers. Crowdworkers collaborate with members of their networks to 1) manage the administrative overhead associated with crowdwork, 2) find lucrative tasks and reputable employers and 3) recreate the social connections and support often associated with brick and mortar-work environments. Our evidence combines ethnography, interviews, survey data and larger scale data analysis from four crowdsourcing platforms, emphasizing the qualitative data from the Amazon Mechanical Turk (MTurk) platform and Microsoft’s proprietary crowdsourcing platform, the Universal Human Relevance System (UHRS). This paper draws from an ongoing, longitudinal study of crowdwork that uses a mixed methods approach to understand the cultural meaning, political implications, and ethical demands of crowdsourcing.

Accounting for Market Frictions and Power Asymmetries in Online Labor Markets

—Sara Constance Kingsley, Mary L. Gray and Siddharth Suri in Policy & Internet, 7(4):383–400, 2015

Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT) is an online labor market that defines itself as “a marketplace for work that requires human intelligence.” Early advocates and developers of crowdsourcing platforms argued that crowdsourcing tasks are designed so people of any skill level can do this labor online. However, as the popularity of crowdsourcing work has grown, the crowdsourcing literature has identified a peculiar issue: that work quality of workers is not responsive to changes in price. This means that unlike what economic theory would predict, paying crowdworkers higher wages does not lead to higher quality work. This has led some to believe that platforms, like AMT, attract poor quality workers. This article examines different market dynamics that might, unwittingly, contribute to the inefficiencies in the market that generate poor work quality. We argue that the cultural logics and socioeconomic values embedded in AMT’s platform design generate a greater amount of market power for requesters (those posting tasks) than for individuals doing tasks for pay (crowdworkers). We attribute the uneven distribution of market power among participants to labor market frictions, primarily characterized by uncompetitive wage posting and incomplete information. Finally, recommendations are made for how to tackle these frictions when contemplating the design of an online labor market.